In this column La Gazzetta will introduce notable members of our local Italian American community. We will hear from men and women whose ancestors’ contributions have resulted in today’s outstanding, productive citizens.

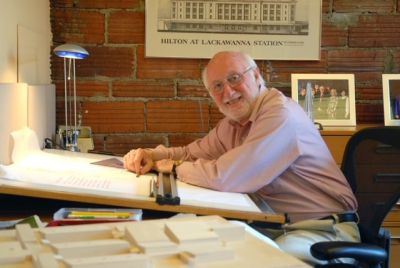

Paul Ricciuti became an architect over 60 years ago. Today his work continues to enhance the built up environment of the Mahoning Valley, as shown by the modernization of Youngstown’s Wick Avenue Corridor. His talented planner’s touch can be seen in our public buildings, such as our schools and libraries.

Paul Ricciuti (PR): I was born in Brownlee Woods, on Youngstown’s Southeast Side, and attended Woodrow Wilson High School. My mother was from Montelongo, Campobasso, in today’s Molise region. And my father hailed from Sant’Eusanio Forconese, in L’Aquila, Abruzzo.

LG: Tell us about the builidngs around Youngstown when you were growing up.

PR: There was the iconic Central National Bank or Central Tower, now renamed SMB Tower, on Public Square. It shows the same style as Rockefeller Center. With, a terra cotta base and cornice, the Realty Building was modeled after Louis Sullivan’s work in Chicago. It now houses condos. I’ve always admired that building.

The Palace Theater and the State Theater are gone, major losses. The McKelvey Building, a classic department store, was unfortunately condemned and taken down. Furthermore, we’ve injured historical buildings by imposing modern “improvements” on them. The Union Bank and the Wick Building recently had flat panels tacked to their exteriors that hide the original lines. After WWII, all the storefronts on Federal Street were modernized, covered in porcelain. This facelift, obliterating the earlier esthetics, changed the whole character of downtown. Warren and Pittsburgh have done a better job maintaining their historic storefronts.

LG: What drew you to the field of architecture?

PR: I always loved to draw. In 11tthh grade I was taking mechanical drawing when a Mr. Volpini came to my class to ask if anyone would copy drawings for him so he could have prints made. I volunteered and was soon fascinated by a process that began with my skill and ended up with an actual creation that was useful to someone. After graduation in 1953, I studied architecture at Kent University, where it took me six years to complete a five-year degree because I took a year off to live in Washington, D. C. to work under a local architect. I graduated Kent in 1959. I thought I’d be an engineer, but I found architecture more creative and esthetically pleasing.

LG: As an architect who has visited Italy on a number of occasions, what has struck you most on your travels there?

PR: Well, let’s start with the Romans and the development of architecture as it relates to the classical buildings that I see in the building practices of that time. They innovated and excelled with the arch, masonry, and stone. For example, I admire the Parthenon with its major and minor axes. It presented to the world a whole new idea of how to erect buildings. From that we move forward to the Renaissance in which architecture for religious uses became predominant. The domes in Florence and Rome and the classical orders still inspire today. It’s a marvel how size and concept came together. The Italians improved on what they inherited from the Romans.

LG: Historically, Youngstown has been home to several notable Italian builders and architects. Could your careers have been built on a common sensibility linked to your Italian heritage?

PR: I think so. There was a certain respect for Italian architects in cities like Youngstown and Pittsburgh. Pat D’Orazio was the first Italian architect of note in our area. When I graduated college I thought of working for him, but his office was located in a very small building on Belmont Avenue. There wasn’t room for another drafting table. Pat was good, with a specialty in designing churches. His work owes a lot to the Beaux Arts style in which he was educated. My professors were from Carnegie Melon in Pittsburgh. When I started college, architecture was drifting toward modernism and away from the Beaux Arts. I was on the cusp of this change.

LG: What’s the use of public space to a city and its citizens?

PR: Well, we all know that in Italy the piazza is where people gather and greet each other. We do that in different ways in the U. S. We have parks, but we’ve never had a public space in downtown Youngstown where people could sit to talk and have coffee. We have Central Square but it’s always had vehicle traffic that confines the space. It’s not a place that welcomes people. In major cities public spaces are critical for the health of the city. Fortunately, we have Mill Creek Park, but you need a car to get there. It’s not in the center of the city, like in Italy.

LG: The design of educational and institutional buildings seems a feature of your career. Can you name a few projects that originated in your studio?

PR: We planned educational buildings for Youngstown State University (YSU), including the Maag Library. We did public schools all over Ohio, from Cleveland to Columbus, and we designed career centers in Mahoning and Trumbull Counties. The new East High School in Youngstown came from our drawing boards

LG: I know that in the 1980s your firm worked to restore the National McKinley Birthplace Memorial in Niles, Ohio. What was involved in returning that monument to its original beauty?

PR: The building was designed by a very famous architectural firm: McKim, Mead, and White of New York, who planned major Beaux Arts buildings in the United States. In 1917, Joseph G. Butler, Jr hired the company to design a memorial for President McKinley. LG: What has been your involvement in the beautification of Wick Avenue?

PR: The first building was the Magg Library at YSU, in 1976, a large edifice constructed on a plinth with five upper stories. We turned the Arms Museum Carriage House into a library and archives. At the Butler Institute of American Art, we designed the new court. Charles Gwathmey was the designer of the McDonough Museum of Art, while I served as the planner. Also I’ve worked on the preservation of St. John Episcopal Church. I helped plan the restoration of the YWCA. The upper floors were converted to provide residences for single women. Our firm did the 1982 addition to the main branch of the Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County.

LG: That’s an impressive list for such a short space. Greater Youngstown has witnessed a steep decline since the mills closed. What can architecture offer a Rust Belt city that’s struggling to rebuild?

PR: Sadly, we’ve gone from a population of 160,000 to 60,00. But the metropolitan area counts 500,000 people. You try to build on what’s already there. Actually, the biggest positive impact on Youngstown includes the following: the growth of YSU, the preservation of a lot of really fine buildings, and the trend in downtown rental and condo units. These are resources for sustainability. Three major conversions have been completed and two more are on the drawing board. The core is being saved because of education, entertainment, and new residences in converted legacy buildings.

LG: Outside your profession, have you been active in the community?

PR: I’ve served on boards of directors: at the Youngstown Symphony Society, Stambaugh Auditorium, and Mahoning Valley Historical Society. I’ve sat on the vestry at St John’s Episcopal Church and have been a trustee for the Tod Homestead Cemetery,

LG: Your civic engagement amounts to another great contribution to Youngstown. It’s wonderful that the constructions you’ve designed and guided enhance urban life here in the Mahoning Valley. Thank you for your time.