At the turn of the previous century, a neighborhood in Atlantic City received a sizable influx of newcomers from Italy. The chicken coops and duck enclosures built by these immigrants gave the area its name, Ducktown. Nowadays, people may know the place from its proximity to Whitehouse Subs, at Arctic and Mississippi Avenues, a famous eatery. The neighborhood has often been called the city’s Little Italy. Today it’s home to a vibrant immigrant population from East Asia and Latin America.

In her recent Atlantic City exhibit at the Noyes Art Garage, ceramicist/painter Janice Merendino returned to the small apartment house and nearby home that belonged to her family in Ducktown. Her paternal side arrived from Sicily in 1904 and her mother’s people from the provinces of Benevento and Caserta around the same time. These two family properties are still standing, lovingly situated in Merendino’s memories. What’s more, they inspired her to capture on paper the material objects and routines of her family in those buildings and to extend that history to include the Bangladeshi and Latino immigrants that reside there today. Here we talk to the artist about her recent exhibit.

La Gazzetta (LG): I saw your Ducktown exhibit in Atlantic City before it closed at the Noyes Arts Garage. It’s remarkable how you wove the Italian American past of those two family properties into the present.

Janice Merendino (JM): It is true that the neighborhood where I grew up is no longer predominately Italian American, but I was constantly struck by similarities between what I remember and what is happening there now. A vibrancy remains. Children still go to the corner store and ask their parents if they can keep the change. Only the candy and prices are different. The barbershops are still an anchor and a gathering place. Neighbors have vegetable gardens, pride in their rose bushes, and keep an eye on the children. Instead of the old Italian ladies sweeping the street, I saw young fathers doing it. I wanted people to visibly see the connection between then and now.

LG: A lot of Italian Americans of my generation feel a sense of loss when we recall the places where our immigrant grandparents first settled. We feel that that era is sadly gone, disappeared into thin air. I didn’t get that feeling at all from viewing your Ducktown exhibit. What idea of immigration were you trying to share?

JM: That we may not be related by blood or ancestry, but we can be related by place. I immediately felt a sense of closeness to the current residents of what was my grandparents’ home. I wanted to show visually how wherever you are standing, someone was probably there before you, and others will come after you. It is so basic, yet it is an idea that gets lost when we look at immigration. I tried to make this point not only through the people, but also by looking at the exact spots that change over time. It was fun to paint images then and now of the furniture changing, while the spot where it once sat remained the same. I did this in several works since I was fortunate enough to have old photos I could compare to the present.

LG: To create this exhibit, you made contact with the current residents of your grandmother’s house?

JM: At my grandmother’s house, my cousin and I first met the young adults of the household since they were more comfortable speaking English, and I could explain this neighborhood art project to them. But in less than an hour of our visit, we were asked to stay for lunch. This was especially emotional for us as we sat in my grandmother’s dining room, served by another family matriarch. The space stayed the same as the people, the new occupants, changed.

LG: What are some of your cherished memories of your grandparents’ house in Ducktown?

JM: Of course there were many memories of family events, but as kids I remember us gathering around my grandfather’s chair. I became intrigued by that one spot in the house and wondered what was there now. In 2021, I painted the spot where my grandfather’s chair sat. Then on a visit with the current occupants, I was happy to find a beautiful vase with flowers decorating his old spot and enjoyed updating it with another painting.

LG: You discovered that the old space never died or disappeared. Is there a work from the Ducktown exhibit that incapsulates that shared space?

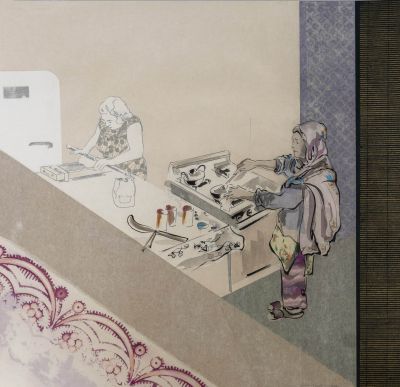

JM: Yes, the image, “In the Same Kitchen, 60 Years Apart.” On most Sundays, my Italian immigrant grandmother rolled out dough for pasta for our traditional family dinner. On a Sunday 60 years later, another immigrant mother from Bangladesh is making samosa in the very same kitchen and inviting me to stay for lunch.

There were many different emotions. I also discovered that the two young people in my grandmother’s house were also artists! I immediately found collaborators who were engaged and interested in the history of their home for the project. It was wonderful to share old photos of the spaces that they lived in and for them to see the other lives that inhabited the same space. There were many laughs when I explained that the young woman’s small bedroom was once the bedroom of three sisters (my two aunts and my mother) who shared a very small closet.

LG: What else did you discover?

JM: My mother and grandmother crocheted doilies. I found out that one of the young artists who lived in the old family home painted beautiful mandalas. I could see that she was creating patterns similar to the doilies women in my family once made, so I collaged her mandalas with doilies in one of my pieces.

LG: You’re a ceramicist, too, but for this exhibit you employed a special kind of paper and ink drawing. Why these media?

JM: I have always straddled both media but chose paintings on paper for this project. Working in clay is a slow process with many steps before completion. I wanted to combine the quickness of the ink brushwork with the slow cutting and mounting of collage work. It satisfied both needs to be loose and spontaneous and tight and deliberate. The process of making the work involves many layers where some aspects are clear and other parts of the image are obscured. The process itself is a metaphor for how clear memories coexist with hints of what has been lost.

Many thanks to ceramicist and painter Janice Merendino.