L’Infinito di Giacomo Leopardi ha compiuto 200 anni: per celebrare adeguatamente uno dei testi poetici più famosi ed amati della lingua italiana, tra le tante iniziative organizzate lo scorso maggio si è svolto a Recanati - cittadina natale del poeta marchigiano - un flash mob di migliaia di studenti giunti da tutta Italia, che hanno recitato in contemporanea questo capolavoro della letteratura, arrivato al proprio secondo centenario e con cui ogni generazione di studenti italiani si è dovuto e si deve a tutt’oggi cimentare sui banchi di scuola. La lirica, breve e potente, è composta da 15 endecasillabi sciolti ed appartiene alla raccolta dei Canti. È uno dei testi più rappresentativi di Leopardi, appartenente al genere dell’idillio e descrive perfettamente quel delicato equilibrio di sensazioni, emozioni e riflessioni. Nonostante i suoi 200 anni, rimane una poesia attuale, esatta descrizione dell’enigmaticità e della complessità umana.

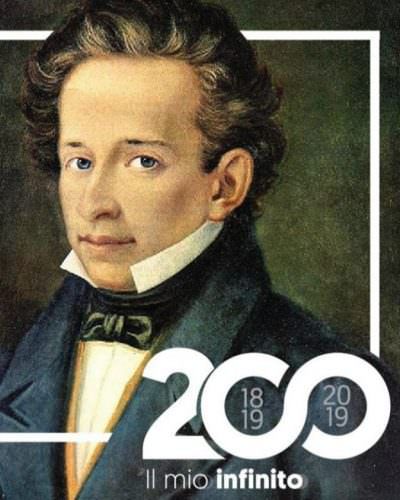

Giacomo Leopardi is one of Italy’s most celebrated poets and his masterpiece, “The Infinite,” written when he was just 21-years-old, celebrates its 200th anniversary this year. A Romantic poet who is not well-known outside Italy, his work reflects his extraordinary genius.

To fully appreciate the poem’s beauty, it is important to understand a bit about Leopardi’s background. He was born in 1798 in Recanati, a small town in Le Marche on the Adriatic coast, the oldest child of an aristocratic family. His father, Menaldo, was an avid collector of books and had a library that was the envy of the local nobility. His mother, Adelaide, was extremely devout, but also rather cold and emotionally distant with her children. It was Adelaide who undertook the task of restoring the family fortune when her husband took on substantial gambling debts. Menaldo wanted his children to receive a comprehensive classical education and hired several tutors for Giacomo, his younger brother Carlo, and, surprisingly, even his sister Paolina at a time when the education of girls was still almost unheard of.

Giacomo was known to be the most diligent of the three, dedicating hours to his studies. At 14, his tutors announced to his father that they had nothing more to teach him and he became an autodidact, eventually learning 6 languages (in addition to Italian, he learned Greek, Latin, Hebrew, French, and English) and translating works by Homer, Virgil and Horace. He studied science, history and the philosophy of the Enlightenment. When he was just 15, he spent 6 months writing an extremely detailed history of astronomy. In addition to his poems and prose, he began keeping a diary in 1817 of notes, reflections and aphorisms, known as “The Zibaldone,” that totaled 4,562 pages when it was published after his death. His father’s library held around 8,000 books and Giacomo was estimated to have read 70% of this collection.

At the time, Recanati was part of the Papal States, whose citizens were forbidden from reading or studying any works included in the “Index librorum prohibitorum” (“List of Prohibited Books”) as they were considered heretical or immoral. The first “Index” was published in 1559 by Paul VI, but over time there were more than 40 editions of the list. During Giacomo’s adolescence, the list would have included authors, scientists and philosophers as wide-ranging as Daniel Defoe, Montesquieu, Locke, Milton, Bacon, Descartes, and Galileo. However, Menaldo received a special papal dispensation for his children to study these books, including his daughter, although they were kept under lock and key in a special cabinet in his library.

Giacomo was a prodigy, a brilliant and keen thinker. However, the hours spent studying by candlelight in his father’s library took a toll on his health, resulting in serious vision problems as well as other issues which kept him inside and largely isolated from other children his age. Around the time “The Infinite” was written, Giacomo tried to escape the confines of his secluded life, obtaining, without his parents’ knowledge, a passport to travel to Milan. Menaldo and Adelaide discovered and thwarted his plan, believing their son too fragile for such a journey on his own. Giacomo was devastated and felt like a prisoner in his own home.

Reading “The Infinite,” it is not hard to envision the delicate young man, staring out the windows of his palazzo at the rolling hills of Le Marche, touched by the beauty of what he saw but longing to experience the world beyond the pages of his books.

Eventually, Giacomo was able to travel and earn some financial independence from his parents with his writing and his work as an editor. He fell in love a couple of times, but it was unrequited, and he never married or had children. A central theme of many of his poems is man’s inherent unhappiness, which he considered a law of nature from which man was unable to escape. He died outside Napoli in 1837, not even 40-years-old, leaving behind a remarkable legacy.

Throughout 2019, Leopardi’s hometown of Recanati is commemorating the 200th anniversary of “The Infinite” with a series of events, such as a photography exhibition that interprets the poem in visual form and even “flash mobs” of students reciting the poem in piazzas across Italy. As explained by Olimpia Leopardi, a descendant from one of Leopardi’s younger brothers, these celebrations serve to “promote the message that Giacomo left with us, that limits should not impede us, but teach us to look beyond, to see the infinite possibilities that lie within us.”